Ten years ago, the world

was in the grip of a panic over an outbreak of a mysterious illness -

Sars. The virus killed hundreds - and infected thousands more - but its

impact would have been far more devastating had it not been for the

bravery of a handful of doctors and nurses.

"It was like a nightmare - each morning you arrived and more people were sick."

In 2003, Dr Olivier Cattin was working at the French hospital in Hanoi, in the north of Vietnam.

"We got to the Friday and there was only one nurse left on

our ward who was able to treat the other nurses, and this nurse was also

sick."

One day at the end of February that year, a Chinese-American

man, Johnny Chen, had arrived with what appeared to be a bad case of

flu.

Within days, nearly 40 people at the hospital had fallen ill,

including a number of the staff. Seven would go on to die. This was the

site where the deadly disease - later named severe acute respiratory

syndrome (Sars) - would come to the attention of the world.

It was highly contagious, and often deadly. More than 8,000 people around the world were infected, and more than 770 died.

Continue reading the main story

Find out more

Kevin Fong was reporting for a two-part

BBC World Service documentary

Sacrifice: The Story of Sars.

Part 2 airs on Sunday at 14:06 GMT (15:06 UK time)

But this is a story about people

not statistics. The closer you get to the story of Sars, the more

overwhelmed you become by the experience, and the heroism, of those who

stood on the frontline.

War is a metaphor that we often use in relation to the fight

against disease. But it is rarely more apt than in the case of Sars.

At the French hospital in Hanoi, panic set in as the doctors

reviewed the X-rays of all those who had fallen ill. They knew they were

facing something very serious and highly unusual.

"All the chest X-rays were abnormal and... were similar to

Johnny Chen. We had a panic attack. We were all thinking that they were

are all going to die," says Cattin.

"One by one, we saw the X-rays and there was a big silence

because we could not talk… We didn't know what was going on. It was

very, very scary."

The virus had a highly unusual pattern of transmission. Its

peak of infectivity occurred late in the course of the disease when its

victims were at their most unwell and usually in hospital care.

Because of this, the worst cases clustered in a few hospital

wards and intensive care units in a handful of major cities. And within

these, the virus spread like wildfire.

When Johnny Chen and some of the first medical staff to care

for him all died, they began to understand what they were facing and the

risk it posed to the world outside.

The 2003 Sars outbreak

|

|

Selected countries

|

Deaths

|

Cases

|

Source: World Health Organization. Cases 1 Nov 2002-31 July 2003

|

China

|

349

|

5,327

|

Hong Kong

|

299

|

1,755

|

Canada

|

43

|

251

|

Taiwan

|

37

|

346

|

Singapore

|

33

|

238

|

Vietnam

|

5

|

63

|

Malaysia

|

2

|

5

|

Philippines

|

2

|

14

|

Thailand

|

2

|

9

|

France

|

1

|

7

|

South Africa

|

1

|

1

|

Total all countries

|

774

|

8,096

|

Full in this knowledge, they took the incredible step of

locking themselves in, quarantining themselves away from the city to

protect it and their country.

"I've never met such amazing doctors and nurses as I did in

North Vietnam," says Cattin. "I lost five colleagues, they were friends.

We're the survivors of this outbreak."

Another survivor is Dr Le Thi Quyen Mai, head of virology at the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology in Hanoi.

"I am very, very lucky," she says. As news of the deadly

virus spread through her institute, most of her colleagues fled, fearing

for their lives. She stayed, despite having a three-year-old daughter

at home.

Why? "Just a duty," she says simply.

In those early days, when events threatened to spiral out of

control, perhaps their most important single asset in the fight against

this outbreak was Carlo Urbani, an Italian expert on infectious diseases

who was working for the World Health Organization (WHO) in Hanoi.

Continue reading the main story

Lock-down in Hanoi

As the news spread of the outbreak at the French hospital in Hanoi, there was uniform panic among the city's residents.

No-one would so much as approach the medical facility. The

street opposite was empty - its shopkeepers pulled their shutters down

and stayed closed. The catering firm that supplied the hospital refused

to deliver.

In the end the French hospital had to get food and drink from

a local hotel - and even then only on the strict condition that they

didn't tell anyone else about the arrangement.

The nurses who remained during the Sars outbreak described

the hospital as having become like a "desert island" - suddenly isolated

and alone in the centre of an otherwise thronging city.

Urbani felt he could not stay in the office as a paper-pushing bureaucrat. As a doctor, he had to help.

It was Urbani who took samples from the patients for analysis

- at great personal risk - and who first alerted the world to the

crisis.

After working tirelessly in the French hospital for several

weeks, he was urged to take a break. And it was then that he discovered

he too had contracted Sars.

"I knew he was getting sicker and sicker," says his eldest son Tommaso Urbani, who was 15 at the time.

"But I hoped from deep down in my heart that he could make it

because he was my father. And I saw him as a strong person, a strong

doctor and thought he was invincible or something like that. So I never

thought that he could die."

But Carlo Urbani did die, two weeks after developing the

illness. Ten years on, Tommaso says he's proud of the sacrifice his

father made.

"I am sure that if he could go back in time, my father would

do exactly the same things. I'm happy for what he did because he saved a

lot of lives."

But although the story of Sars started in Hanoi, it didn't end there.

Johnny Chen, the first patient to arrive in Vietnam suffering

with the virus, was an international businessman who had arrived from

abroad. And so the trail of Sars lead away from Vietnam back to its

original point of explosion - Hong Kong - where Chen had stayed shortly

before.

Continue reading the main story

“Start Quote

I wrote a note to my children. I said, 'I've been exposed, this might kill me'"”

Dr Monica Avendano

"There were two dozen of my

colleagues sitting in the same room, everybody was shaking and running a

high fever, many were coughing," says Prof Joseph Sung who was head of

the Prince of Wales' medical faculty at the time, and was effectively

the man in charge of this unfolding disaster.

"That was the beginning of the nightmare, because from that

day on, every day we saw more and more people developing the same

illness."

Sung divided his team into two groups. One would care for the

other patients in the hospital, and the second team - the "dirty team"

as they called it - would undertake the dangerous job of treating these

patients, and risking infection themselves.

Anyone with young children was given an exemption from the

"dirty team". But those who were single, and those whose children were

grown up, were encouraged to step forward.

Not only did volunteers step forward - they kept on coming during the weeks that followed.

"I needed a continuous supply of manpower to go in. And I was

very touched by the fact that after we exhausted everybody in the

medical department, surgeons, orthopaedics people, gynaecologists, even

ophthalmologists came to help us."

Sung himself ended up spending three months inside the hospital.

In Toronto, half a world away from the East Asian locations

where Sars first arose, the virus took them completely by surprise.

At the Scarborough Grace hospital, a single patient, arriving

unwell with what initially looked like a severe pneumonia, went on to

infect dozens of staff.

Continue reading the main story

“Start Quote

I had Sars - it's left a lasting impact on me and my life. It's still there for me”

Bruce England

Paramedic

Many were transferred to an old tuberculosis hospital on the outskirts of Toronto for quarantine and treatment.

And as in Hanoi and Hong Kong, there were those who chose to

flee and those who turned up for work one day and stayed - without

returning home - for weeks.

"I wrote a note to my children," says Monica Avendano, a

physician and specialist in respiratory diseases at Toronto's West Park

Healthcare Centre, who was one of those who decided to stay.

"I said: 'I've been exposed, I might get infected, this might

kill me and if it does, don't cry too much. I did it because I'm a

physician and I'm a doctor and my duty is to look after sick people.'"

Dr Avendano did survive, but the experience of Sars in Toronto was nothing if not terrifying for those involved.

Monica Avendano and a colleague at the height of the crisis in Toronto

Monica Avendano and a colleague at the height of the crisis in Toronto

Bruce England was a paramedic on duty in Toronto during the

early days of the Sars outbreak and, having attended a patient with a

chest infection, found himself falling ill.

For him, and many others affected by the Sars outbreak in

Toronto, the effects of that experience are still being felt today. Ten

years on Bruce still experiences weakness and difficulty with his

breathing.

"I had Sars. It's left a lasting impact on me and my life. So did I survive it? Maybe not, it's still there for me," he says.

By the summer of 2003 the chain of human-to-human

transmission had been broken. Doctors had come to understand when the

most contagious times were for anyone infected and what precautions to

take to avoid passing it on.

But what happened in Hong Kong, Vietnam and Toronto could so

easily have happened in London, New York or any destination reachable by

plane.

The vectors of this virus were not rats on ships but aircraft

travelling at hundreds of miles an hour across the globe. The reason

that this is an important story to tell and to continue to retell is

because of how narrowly disaster was averted.

And I now think that the margins were much narrower than we ever realised.

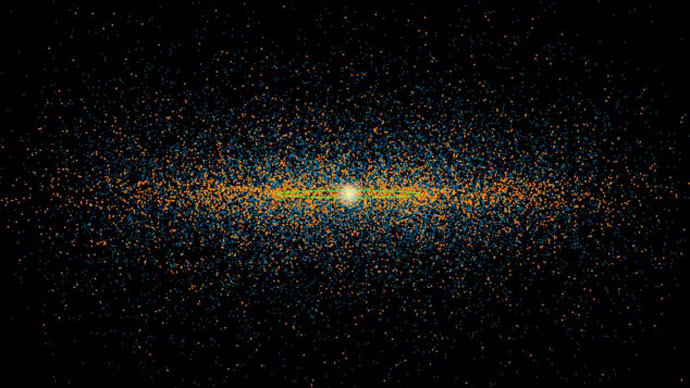

This graphic shows the orbits of 1,400 Potentially Hazardous Asteroids (PHAs). (Photo by NASA)

This graphic shows the orbits of 1,400 Potentially Hazardous Asteroids (PHAs). (Photo by NASA)

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange.(Reuters / Suzanne Plunkett)

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange.(Reuters / Suzanne Plunkett)